An Inside Look at Cadaver Lab

Published

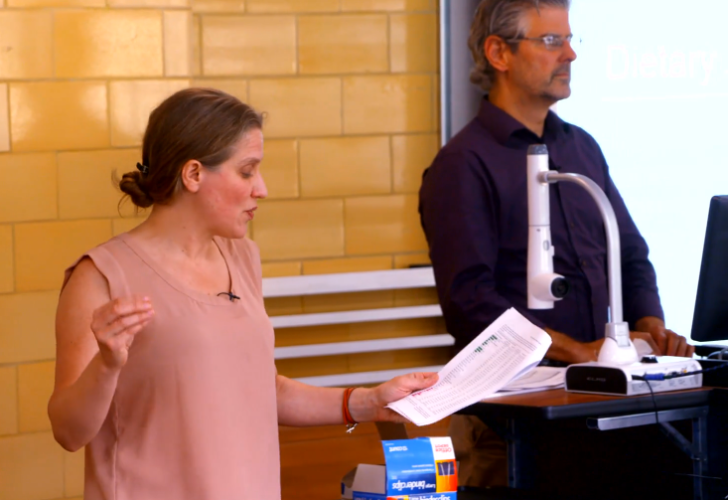

A tall woman strides into the Bastyr University auditorium during Orientation Week in September, clad head-to-toe in a white isolation suit. She turns to the class of new students, lifting her respirator mask and goggles. Then she smiles.

"Welcome to the anatomy lab fashion show," she says.

The class laughs. Tense shoulders relax a little. One of the most intimidating parts of naturopathic medical school begins with a calming word.

That's typical of Rebecca Love, DVM, a faculty member in the Department of Basic Sciences, who will guide naturopathic medicine students through their year-long work dissecting human cadavers.

In Gross Human Anatomy Lab, or Gross Lab, the class joins first-year medical students across the country in wielding scalpels to learn lessons that books cannot teach. The process is terrifying for some students and exhilarating for others. Most say it is deeply significant in some way — transforming their understanding of the human body, or their own fears, or their new identity as healers-in-training.

"It's the best learning tool," says Shasta Ward, a second-year student. "Everything I learned goes back to the Gross Lab."

"I was pretty terrified, to be honest," classmate Chantz Richards says of his first day in the lab.

Meet Your First Patient

The class begins in the auditorium, where Dr. Love explains how students can care for their own bodies while working near formaldehyde, a toxic preservative. Unlike most medical schools, Bastyr requires "bunny" suits and masks for protection — a product of the naturopathic emphasis on avoiding environmental toxins. Students also learn about milk thistle and other herbs they can take to support the liver's detoxification function.

The class begins in the auditorium, where Dr. Love explains how students can care for their own bodies while working near formaldehyde, a toxic preservative. Unlike most medical schools, Bastyr requires "bunny" suits and masks for protection — a product of the naturopathic emphasis on avoiding environmental toxins. Students also learn about milk thistle and other herbs they can take to support the liver's detoxification function.

Then Dr. Love tells them about the bodies. They are taught to view the cadaver as their first patient, learning to read the body for the story it tells about health and illness.

Most importantly, Dr. Love tells them these cadavers are gifts — donations from former people who chose to give their bodies to medical education. A donation program in Texas sets regulations for the bodies, which are cremated and returned to families at the end of the year. During the first lab, Dr. Love leads a ceremony for students to reflect and thank the people who have given their bodies. Remembering that the bodies were given as gifts can help students grow more comfortable with their work.

"Knowing that they dedicated themselves to our education helped me get through it," says Brianna Vick, another second-year student.

The Cut

Later that day, the class visits the empty lab on the ground floor, where sunlight filters through a bank of opaque windows. Potted ferns filter the air, absorbing formaldehyde and releasing oxygen.

Later that day, the class visits the empty lab on the ground floor, where sunlight filters through a bank of opaque windows. Potted ferns filter the air, absorbing formaldehyde and releasing oxygen.

Students work in teams of three or four, signing up for bodies based on age, cause of death and occupation. Ward chose a man who died of lung cancer, since she had worked with cancer patients in West Virginia before coming to Bastyr. Vick chose a woman that had died of Lou Gehrig's disease. Her uncle died of the disease when she was a teenager, and studying the body was a way to grasp what he went through, she says.

Richards chose the body closest to the door — so he could escape if he panicked, he says. On the first day of class last year, he stared at the floor, trembling. His lab partners were patient, which made things much better, he says. By the third week, he made his first cut. By the end of the year, he knew that the body on the table had changed him.

"I learned that it's OK to be vulnerable," he says. "I could accept that fear might be there, but it doesn't have to limit me."

He told Dr. Love he was willing to speak to new students who struggled with fear.

"Dr. Love is very skilled at what she does," he says. "She knows how to talk to students and gradually introduce things in a way that makes them less frightening. She has a calming presence about her."

His classmates agree — Dr. Love has been the top-rated teacher in student satisfaction surveys over the last three years.

Each Body a Story

Dr. Love, for her part, returns each year excited about what she'll learn herself.

Dr. Love, for her part, returns each year excited about what she'll learn herself.

"Every cadaver has something new to teach me," she says. "I see myself more as an art docent. I tell students: 'I'm not really here to teach you. These cadavers are the teachers. I'm here to help you appreciate the art and science of the human body, including your own body. It's going to be your job to help others appreciate theirs.’"

Dr. Love grew up collecting and dissecting road-kill in rural Massachusetts. She studied physical education, nursing and zoology and earned a doctorate in veterinary medicine. She learned to dissect many species of mammals, some of which are anatomically similar to humans — "Sometimes shockingly so," she says.

At the same time, it's the variations in human bodies that continuously astound those who work in Gross Lab. Where anatomy textbooks say there should be one artery, a body might have two. Where students expect to find two kidneys, there may be only one.

"You learn that what you find in books is not what you find in real life," says Ward, who will help as Gross Lab teaching assistant this fall.

Her "first patient," an 89-year-old man, was a home builder missing a finger, with a fracture in his arm and two knee replacements. Studying his body taught Ward a surprising amount about his life.

"He was a man who had really lived," she says.

Candy and Cheers

Of course, as with any class, there are tests. The first midterm exam falls near Halloween, and advanced students hand out "skeleton" candy to the first-year students to ease the stress. (They often offer fruit and nuts and chair massages, too.)

For the exam, Dr. Love places numbered pins in the bodies. Students must identify the body part, its function or the muscle or tendon to which it connects. Before the test, Dr. Love dims the lights for a moment of silence, reminding students of the sacred gift represented by each body. After the first exam each fall, students leave the lab to find upperclassmen cheering in the hallway, congratulating them.

At the end of the year there is another ceremony to honor the people who gave their bodies. Students can offer artwork and letters in gratitude. Student JooRi Yun wrote a tender poem last year, writing, "I do not know what made your heart burst with love, but I have pictured how the blood flowed through the four chambers of your heart … I do not know all the burdens you carried on your shoulders, but I have cut through the tension you carried there."

For students who carry their own tension, the lab is open between classes to put in extra study, or to simply sit with their cadaver and reflect. Many, like Ward, find the work brings its own energy. When she first touched an enlarged lymph node, a swollen oval in the neck, she thought of past cancer patients, and future patients she would serve.

"This lab is where I tied everything together," she says.