Alumnus Uncovers Ancient Medicine Along Silk Road

Published

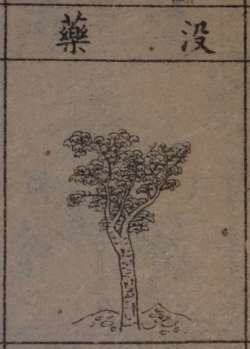

The first known medical use of myrrh, an aromatic resin from the Commiphora tree, appeared in Greek texts in the 5th century B.C. Healers used it to treat topical wounds. Over centuries, it spread across central Asia and throughout China, where it appeared in medical texts a thousand years later as a balm for injuries such as falls from horses.

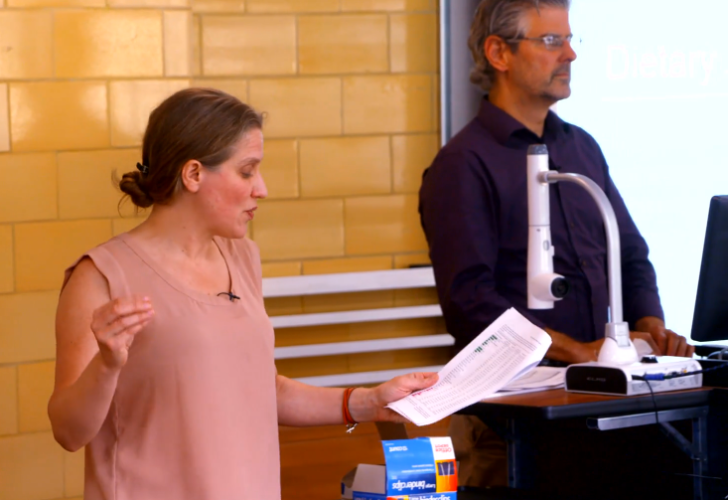

Bastyr University alumnus Sean Bradley, ND (’08), MSAOM (’08), EAMP, is retracing myrrh’s path through medical guides and other texts from the ancient world. It’s part of a larger collaboration to unearth forgotten knowledge from the texts of traditional East Asian medicine.

"We think of medical research as lab and clinical work, but scholarship going back to ancient texts can discover medical knowledge that has been lost over time,” says Dr. Bradley, a research investigator at the Bastyr University Research Institute and practitioner at Seattle Asian Medicine and Martial Arts.

Studying ancient medicine has already yielded discoveries that have reshaped health care. Aspirin pills are related to a compound in willow bark, which Native Americans chewed to relieve pain. Artemisinin, the basis for a widely used malaria therapy, comes from sweet wormwood, a traditional Chinese medicine. The scientist who developed the drug received a prestigious Lasker Foundation prize in 2011.

Studying ancient medicine has already yielded discoveries that have reshaped health care. Aspirin pills are related to a compound in willow bark, which Native Americans chewed to relieve pain. Artemisinin, the basis for a widely used malaria therapy, comes from sweet wormwood, a traditional Chinese medicine. The scientist who developed the drug received a prestigious Lasker Foundation prize in 2011.

By studying myrrh, Dr. Bradley hopes to shed light on how medicine spread and evolved throughout antiquity. He recently presented his research to the International Society for the History of Medicine at its conference, The Great Silk Road and Medicine, in Tbilisi, Georgia. He spoke about how myrrh moved from culture to culture on the Silk Road network of trading routes, medical knowledge traveling along with the resin itself. His talk received a best presentation award.

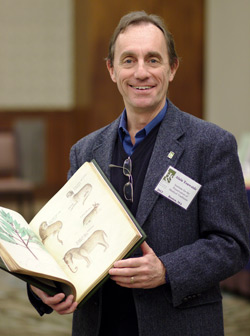

Dr. Bradley is working with a leading authority on ancient medical texts, Alain Touwaide, PhD, of the Institute for the Preservation of Medical Traditions, hosted by the Smithsonian Institution. A historian proficient in 12 languages, Dr. Touwaide has searched through ancient botanical texts, primarily in Greek, Latin and Arabic. He discovered 2nd century Greek references to eating broccoli to treat intestinal cancer, a relationship modern researchers are now investigating. He has built meticulous databases detailing where and how plants are mentioned, enabling medical researchers to test long-forgotten medicines.

East-West Meeting

That approach to cataloguing ancient medicine caught the interest of Dr. Bradley. He will use the same method with East Asian medicine, which has an even larger body of ancient texts than the Mediterranean world.

That approach to cataloguing ancient medicine caught the interest of Dr. Bradley. He will use the same method with East Asian medicine, which has an even larger body of ancient texts than the Mediterranean world.

Building such databases is “deeply important for the study of worldwide botanical medicine,” Dr. Bradley says.

The two met at Bastyr University’s Kenmore campus in 2011, when Dr. Touwaide spoke as a visiting scholar through the William A. Mitchell, Jr., ND, Memorial Fund for Botanical Medicine. Dr. Bradley attended his talk on the resurgence of herbal medicine in the age of pharmaceuticals and found himself drawing parallels to his own research interests.

The two arranged a collaboration with the help of Timothy C. Callahan, PhD, Bastyr’s senior vice president and provost. Dr. Touwaide is also working with botanical medicine professor Eric Yarnell, ND (’96), on a study of ancient herbal treatments for urology issues.

“This is an exciting way to build on the work Dr. Touwaide has been doing for more than 30 years cataloguing the uses of medicinal plants throughout history,” says Dr. Callahan.

The Movement of Knowledge

Dr. Bradley’s path to the Silk Road started with his childhood interest in martial arts and a hapkido teacher who taught him ways to prevent and heal injuries. He enrolled in Bastyr’s Doctor of Naturopathic Medicine and Master of Science in Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine, teaching hapkido, a Korean martial arts form, to classmates on campus, often at 6 a.m.

Dr. Bradley’s path to the Silk Road started with his childhood interest in martial arts and a hapkido teacher who taught him ways to prevent and heal injuries. He enrolled in Bastyr’s Doctor of Naturopathic Medicine and Master of Science in Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine, teaching hapkido, a Korean martial arts form, to classmates on campus, often at 6 a.m.

“That’s the only time everyone was free,” he says.

After graduation, he founded his practice in Seattle’s Lake City neighborhood. The clinic offers both medicine and classes in martial arts and movement therapies such as tai chi and qi gong.

As he studied Chinese herbs at Bastyr, Dr. Bradley grew hungry for more extensive translations of medical texts. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Chinese at the University of Washington and began a master’s program in Chinese literature, learning about vast repositories of ancient texts in China. Chinese universities and libraries have their own collections of ancient medical texts but English translations are often lackluster or nonexistent, he says.

His research on myrrh underscores the need to study medicine across cultures. The resin is native to the Arabian Peninsula (its name is Arabic for “bitter”), though its first recorded mentions are in the writings attributed to Hippocrates.

“To begin I focused on its use in Greek and Chinese medicine,” he says. “The next step is seeing if I can fill in the pieces in between, which would involve ayurvedic medicine, Persian medicine, Tibetan medicine and Arabic medicine. They all have records, although not as extensive.”

Medicine Across Cultures

A cross-cultural approach is crucial for understanding how medicine developed, says Dr. Touwaide. “The study of the history of medicine is very compartmentalized,” he says. “That’s completely wrong. Chinese, Tibetan, Indian, Arabic and Greek medicine were not isolated. They exchanged information and methods and concepts.”

A cross-cultural approach is crucial for understanding how medicine developed, says Dr. Touwaide. “The study of the history of medicine is very compartmentalized,” he says. “That’s completely wrong. Chinese, Tibetan, Indian, Arabic and Greek medicine were not isolated. They exchanged information and methods and concepts.”

Dr. Bradley found that myrrh’s uses were remarkably consistent between Greece and China centuries later. The resin was most often used for treating injuries and also for gynecological uses such as postpartum pain. It was also used to treat eye disorders such as trachoma.

Today, it is mainly used in Chinese medicine for topical injuries. Martial arts fighters apply formulas containing myrrh to their striking hands for protection from injuries, a technique Dr. Bradley teaches at his clinic.

Other historical uses of myrrh changed suddenly, a mystery Dr. Bradley plans to investigate further.

“Those changes could be a case of misidentification,” he says. “It could be at some point in history they got the plant wrong.

“It’s very much an act of discovery.”